Wild Things

A journey through five centuries of art, from Bosch’s monsters to Sendak’s beasts, and what they reveal about how humans build meaning and what happens when it breaks.

by Conrad Phillip Kottak

Introduction: Bizarroland Is Not New

My column, Reflections on Bizarroland, takes its name from a comic-book inversion: Bizarro, the failed Superman who inhabits an upside-down world where logic runs backward and contradiction carries no cost. What once felt like parody now feels uncomfortably close to a description of reality.

In 2025, many of the assumptions that once anchored public life feel unstable. Shared facts are contested. Institutions meant to restrain power bend or break. Language circulates freely but binds little. Authority often behaves erratically and theatrically, with few consequences. The rules still exist, but they no longer reliably organize behavior.

This condition is not new. It recurs.

Long before anthropology became a formal discipline, artists were already studying what happens when systems of meaning fail. They did not use data or fieldwork. They used images. Monsters, ruins, towers, masks, broken bodies, and children’s fantasies appear whenever moral, social, or symbolic frameworks can no longer hold.

The “wild” in this essay does not mean nature opposed to civilization. It names what emerges when human systems stop working. In that sense, Bizarroland does not begin with modern politics.

Bizarroland begins with Bosch.

Bosch and Bruegel: Disorder Inside Order

At the turn of the sixteenth century, Hieronymus Bosch painted a world under strain. The Garden of Earthly Delights (c. 1490–1510, Museo del Prado, Madrid) shows bodies losing boundaries, pleasure sliding into punishment, and desire escaping restraint. The painting is not subtle, and it is not merely moralizing. It reveals anxiety about whether moral order can still command belief. Bosch’s monsters are not outsiders. They are symptoms.

Pieter Bruegel the Elder carried this attention to instability into social life. In The Peasant Wedding (1567, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna), eating and celebration appear ordinary, even joyful, but they depend on shared rules. Culture holds only as long as those rules are recognized.

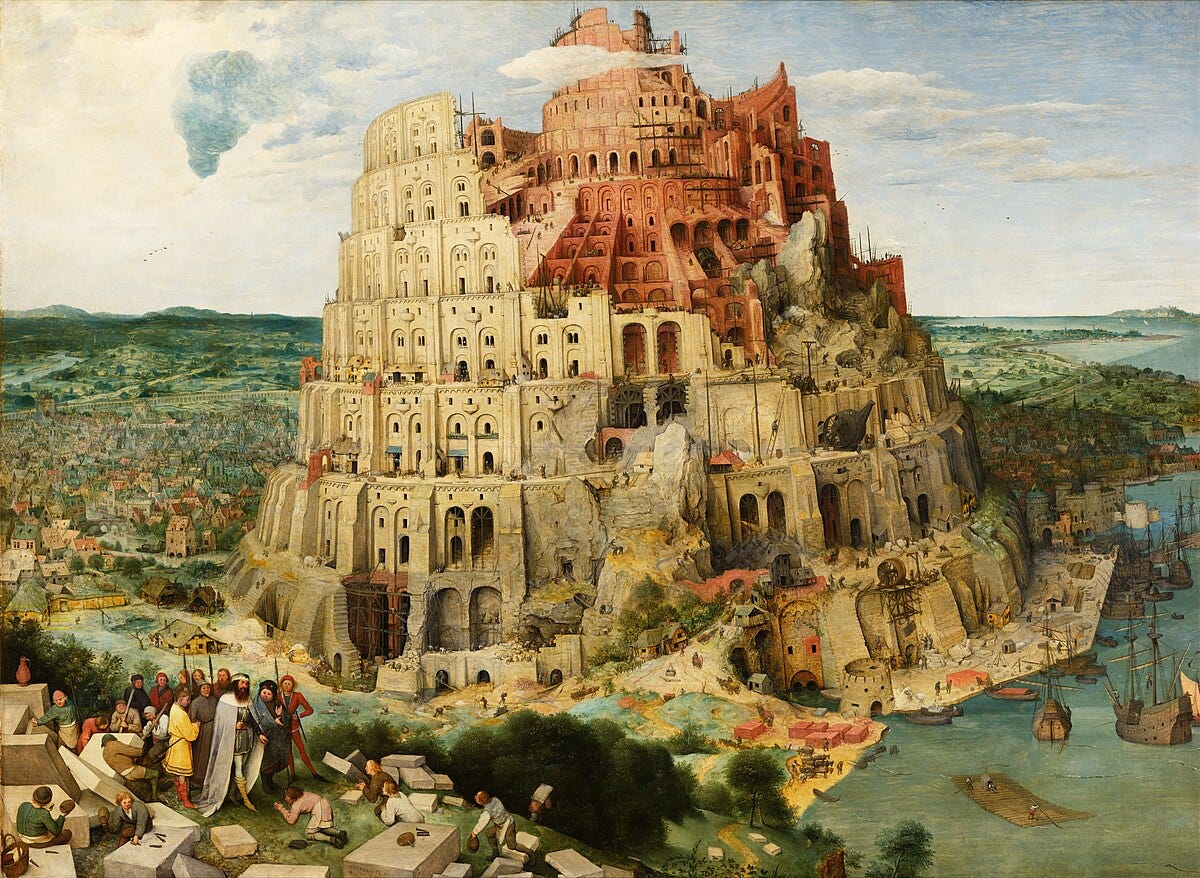

Bruegel addresses this directly in The Tower of Babel (1563, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna). According to the biblical story, God punishes human pride by confounding language. Bruegel’s painting emphasizes something equally unsettling. The tower already shows signs of failure. Foundations do not align. Coordination strains. Even before divine intervention, the project appears internally unstable.

The image suggests a civilization that can still build but can no longer sustain shared meaning. Ambition outruns cohesion. Language, the tool that makes cooperation possible, breaks down. What follows is not instant catastrophe, but confusion.

This is the first clear map of Bizarroland: effort continues, structures rise, but understanding weakens.

Rousseau: The Fantasy of Harmless Danger

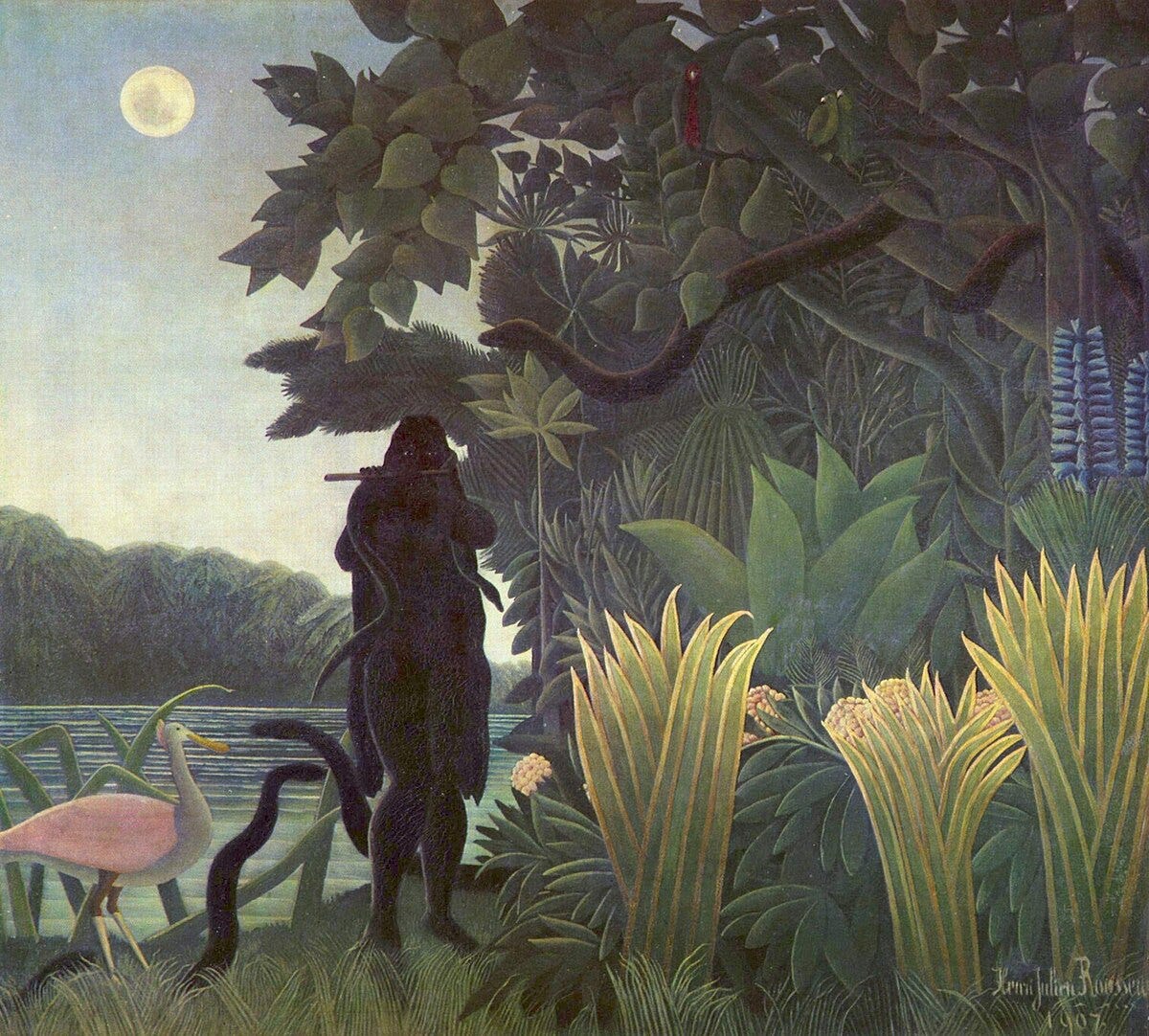

Three centuries later, Henri Rousseau returned to the wild from inside industrial Paris. He never traveled abroad. His jungles were assembled from botanical gardens, illustrated magazines, and colonial exhibitions.

In The Sleeping Gypsy (1897, Museum of Modern Art, New York), a lion stands over a sleeping woman and does nothing. In The Snake Charmer (1907, Musée d’Orsay, Paris), snakes gather calmly around a flute player. These paintings do not describe nature. They imagine danger without consequence.

By Rousseau’s time, anthropology had become a discipline of classification and display. His paintings reflect that environment but soften it. The wild becomes quiet, static, and safe. Threat exists, but it does not act.

Like Bruegel’s tower, Rousseau’s world looks coherent from a distance. Up close, it is a fragile construction made from fragments. Plants, animals, and people coexist without tension because tension has been removed.

This is Bizarroland as denial: a world that appears peaceful because it refuses to acknowledge risk.

Picasso: After Babel

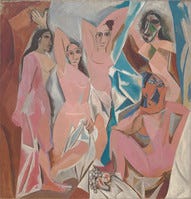

When Pablo Picasso painted Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907, Museum of Modern Art, New York), he was not refining tradition. He was breaking it. Bodies fracture. Faces harden into mask-like forms. Perspective collapses. The painting resists coherence.

Picasso encountered African masks at the Trocadéro Museum in Paris, where they were displayed as ethnographic objects, stripped of their original social contexts. What struck him was expressive force rather than cultural understanding. The encounter reinforced his sense that Western visual language had exhausted itself.

This was not an attempt to recover harmony. It was an admission that harmony no longer held. The fractured forms in Les Demoiselles reflect a world in which shared symbolic frameworks were already failing.

In Guernica (1937, Museo Reina Sofía, Madrid), distortion serves a different purpose. The painting responds directly to a historical event: the bombing of the Basque town of Guernica during the Spanish Civil War. Fragmentation becomes a way to register violence, grief, and terror that resist conventional representation.

Bruegel imagined the breakdown of shared language. Picasso shows what it looks like when that breakdown enters history.

Kahlo: Fracture Carried in the Body

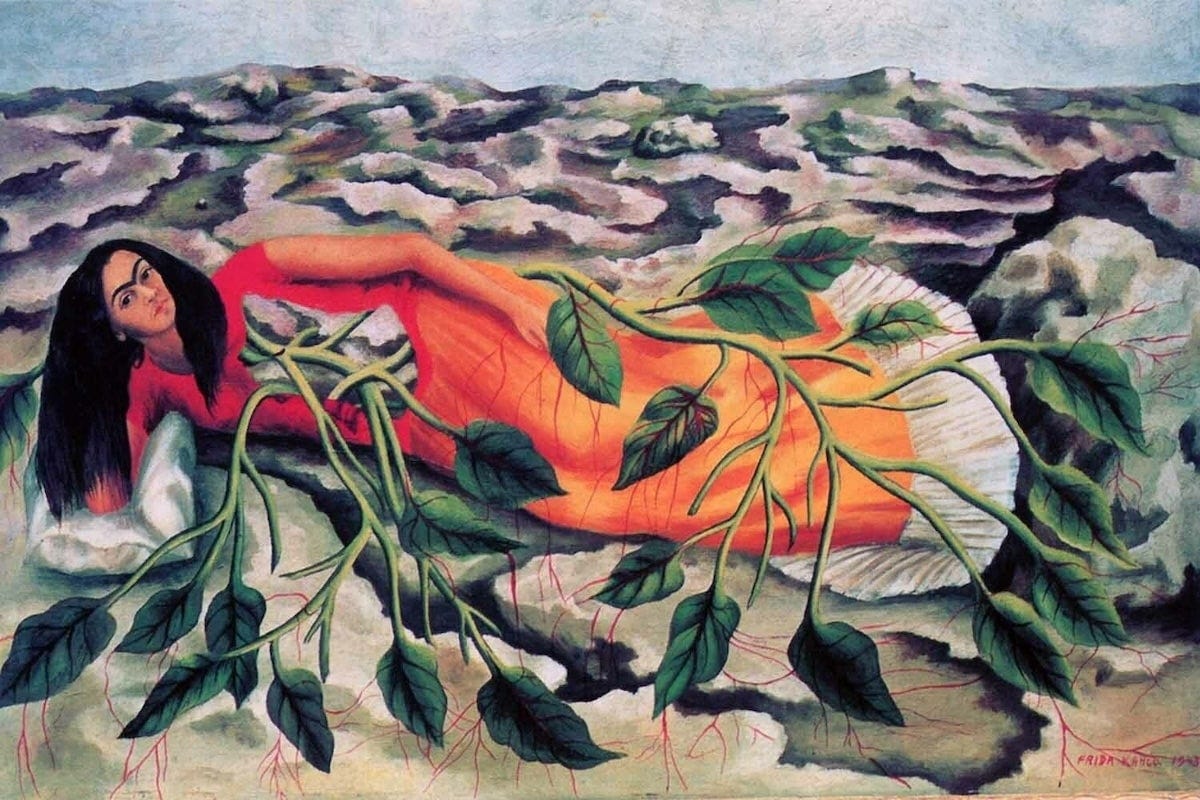

Frida Kahlo does not treat collapse as spectacle. She treats it as lived fact. Her paintings locate cultural fracture in the body itself.

In The Two Fridas (1939, Museo de Arte Moderno, Mexico City), identity is split and bleeding. In Roots (1943, private collection), the body merges with the earth. History, pain, and belonging are inseparable.

Kahlo insists on a basic truth. Culture is not external. It is internalized. When social or historical systems fail, they do not fail abstractly. They fail inside people.

There is no fantasy of escape here. Bizarroland is endured.

Sendak: Containment Instead of Control

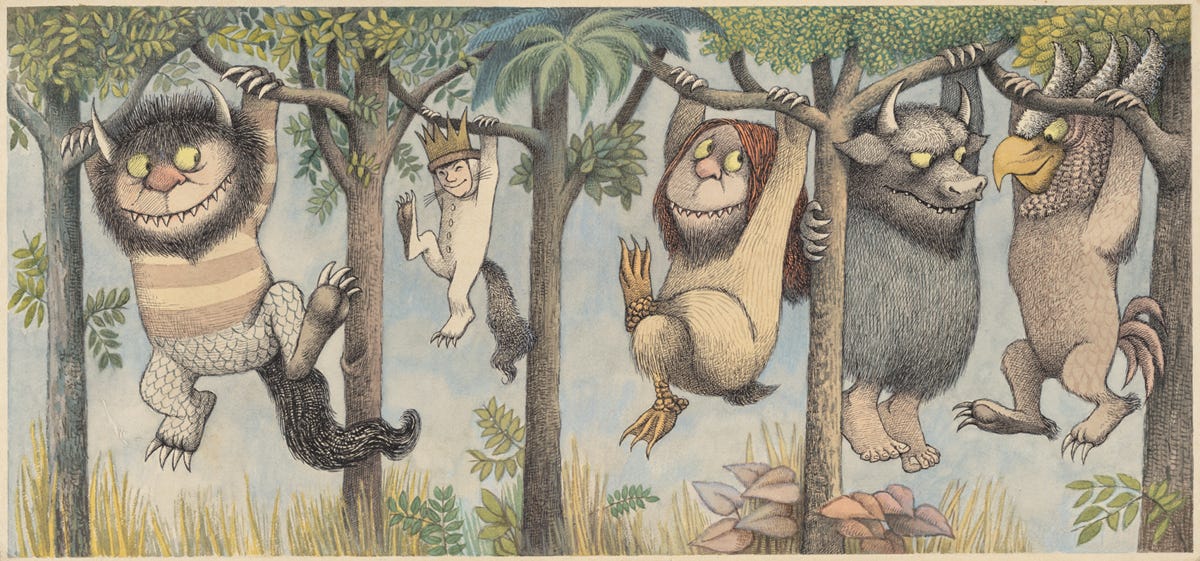

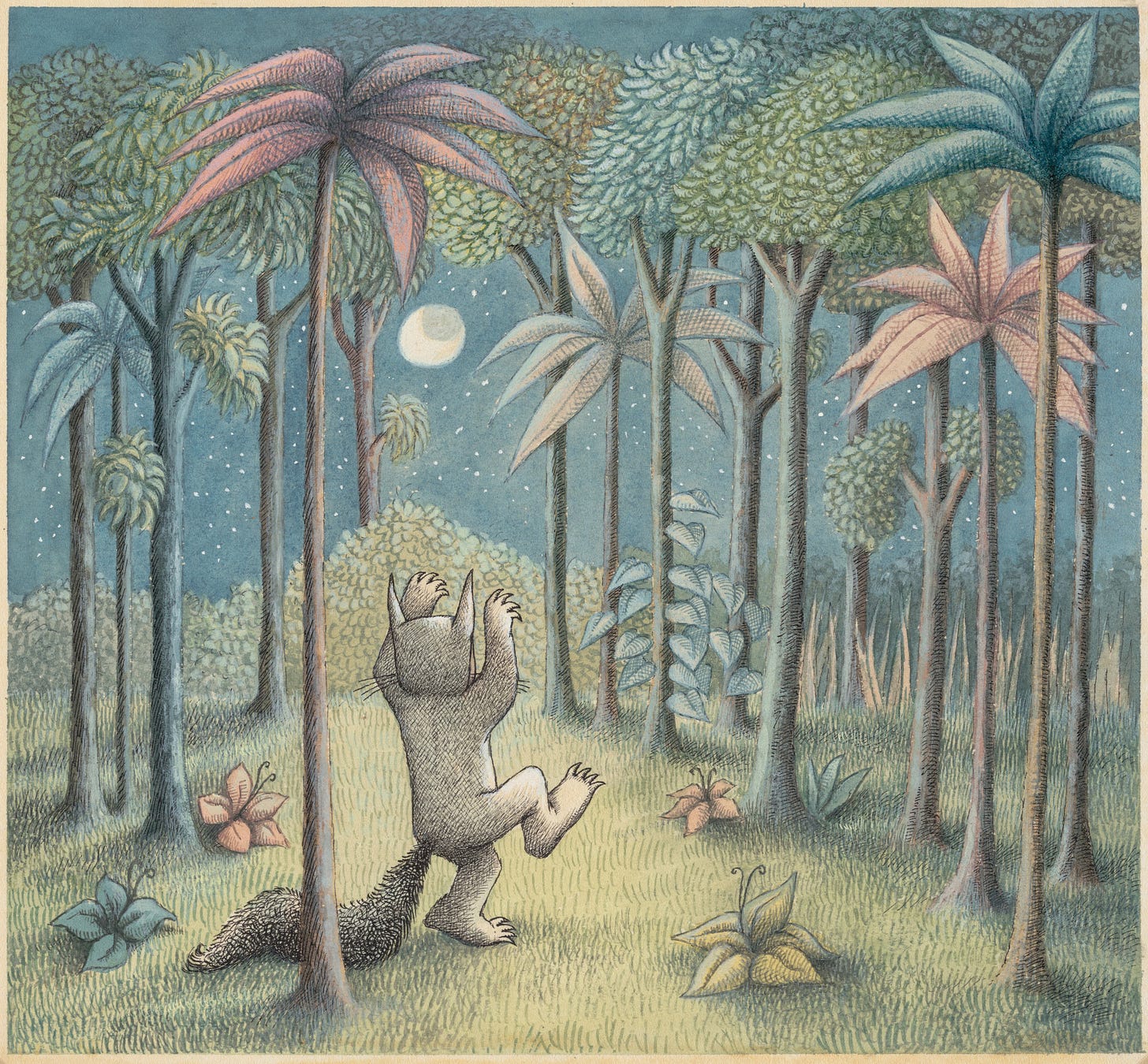

In Where the Wild Things Are (1963; original drawings held at The Rosenbach Museum and Library, Philadelphia), Maurice Sendak tells a simple story. A child misbehaves. He is sent away. He becomes king of monsters. Chaos follows. He returns home.

The wild things are not villains. They are impulses without structure. Sendak’s insight is straightforward. When authority loses restraint, disorder follows. When restraint returns, life becomes manageable again.

This does not make Bizarroland disappear. It makes it navigable.

Conclusion: Why Bosch Still Matters

Across five centuries, artists have returned to the same problem. What happens when the systems meant to organize human life weaken or fail?

Bosch shows desire escaping moral order.

Bruegel shows ambition and language pulling civilization apart.

Rousseau shows danger neutralized through fantasy.

Picasso shows fragmentation after coherence is lost.

Kahlo shows damage absorbed into the body.

Sendak shows the fragile work of containment.

These works are not predictions. They are recognitions.

Bizarroland is not chaos. It is inversion. Rules remain, but they no longer guide behavior. Language persists, but it no longer binds. Power continues, but restraint fades.

The Tower of Babel still stands, not as architecture, but as noise. Bosch’s monsters still walk among us, not as fantasies, but as habits.

Contemporary Coda: Bizarroland Now

The reason these works still matter is simple. The conditions they describe are no longer confined to art. We now live amid the noise Bruegel imagined, the denial Rousseau painted, the fragmentation Picasso recorded, and the tantrum authority Sendak warned against. Public language no longer binds action. Power performs rather than governs. Contradiction carries little cost.

This is not a failure of intelligence. It is a failure of restraint. When leadership behaves impulsively and institutions stop enforcing limits, the wild does not disappear. It moves to the center. Bizarroland becomes ordinary life.

Bosch understood this. He did not imagine monsters because the world was orderly. He painted them because order was already slipping. His lesson was not that chaos arrives from outside, but that it grows when meaning is allowed to decay.

That is where we are now. And that is why these images still speak.

Wow, Conrad—that is both sweeping and insightful (two adjectives that rarely go together, in my experience.) I’m currently (slow) reading a book by a Colombian anthropologist, Carlos Granés, that walks through Latin American painting, poetry, and politics through the long 20th century—1899s to now (as shaped by economic , hence political elites, a world I was not educated in, which has always puzzled me), and I’m finding it fills holes that I could not work around, particularly the Romantic underpinnings of the political *right*. There’s a reasonable representation of Brasil, though it flows effortlessly across borders (which I’m also finding useful.). Title: Delirio Americano.

Hello from another Boschian Substacker who sometimes writes about wild things!